COVID-19 , Endpoint Security , Fraud Management & Cybercrime

Employee Surveillance: Who's the Boss(ware)?

Pandemic Drives Increased Adoption of Workplace Monitoring Tools

How big is the "employee surveillance business"?

See Also: Maintaining Your Mission: The Need for Complete Cyber Protection

With so many more employees now having to work from home during the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous organizations have been exploring the use of employee-monitoring tools.

Proponents say such tools can help companies manage remote teams, maximize billable hours and spot idle workers - for example, salespeople who are failing to contact or visit prospects. Such tools may also help enforce security policies to better prevent home workers from getting hacked and corporate data being exposed.

But critics warn that employee-monitoring software can be overly intrusive. And in regions of the world where individuals enjoy strong privacy protections, such as Europe, using such tools non-transparently - or in a not well-documented or well-reasoned manner - may also expose organizations to legal and regulatory risks.

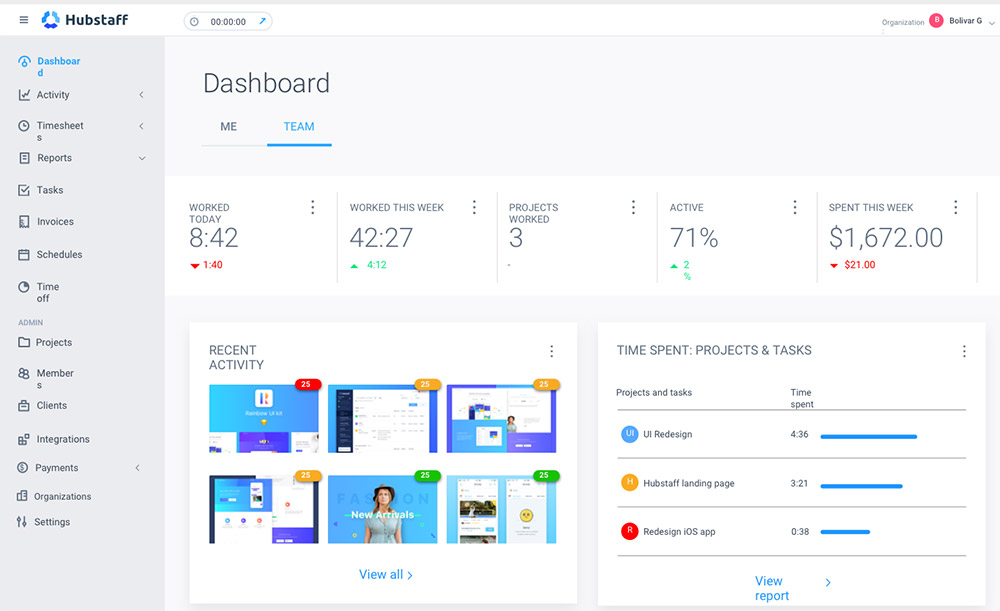

Many different types of software may include monitoring capabilities. But looking specifically at the time-tracking and productivity monitoring space, big players include Hubstaff, Sapience and WorkSmart. Others named in a recent PC Magazine roundup include ActivTrak, DeskTime Pro, Hubstaff, InterGuard, StaffCop Enterprise, Teramind, Time Doctor, Veriato, VeriClock and Work Examiner.

Many time-tracking and productivity-monitoring software vendors have reported soaring interest since lockdowns went into effect earlier this year. In May, Dave Nevogt, CEO of Hubstaff, told the New York Times that trials of his company's software, which carries a per-user monthly cost of $7 to $20, had tripled since March.

Also in May, Brad Miller, the CEO and chairman of Awareness Technologies, which owns InterGuard, told ABC News that his company's customer base had tripled or quadrupled since lockdowns began.

From Light Touch to Big Brother

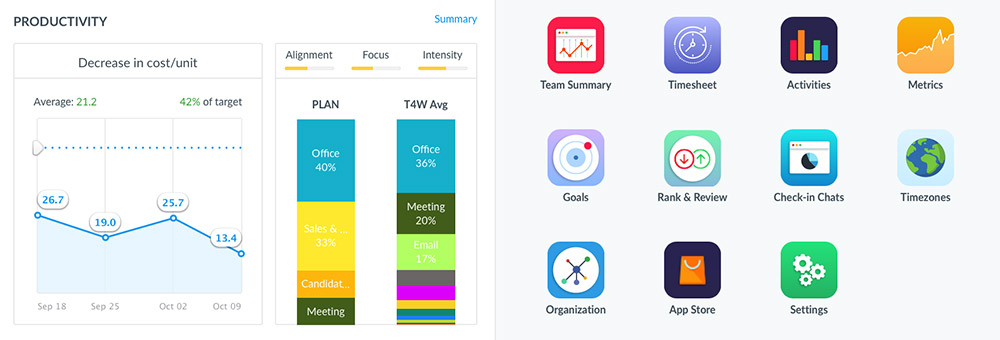

Employee-monitoring tools include relatively light-touch options that try and track productivity by looking at how much time employees spend using "work" software.

On the more Big Brother end of the spectrum, some software can record audio and video of users, log keystrokes, use optical character recognition to record any text that appears on screen, and monitor email, chat discussions and social media posts, among other capabilities.

Electronic Frontier Foundation, a non-profit digital rights group based in San Francisco, collectively refers to all workplace monitoring tools as "bossware," and says they can pose a fundamental risk to workers. "While aimed at helping employers, bossware puts workers’ privacy and security at risk by logging every click and keystroke, covertly gathering information for lawsuits, and using other spying features that go far beyond what is necessary and proportionate to manage a workforce," EFF says in a recent blog post.

But not all monitoring is bad. Data loss prevention software, for example, can help organizations prove their compliance with data-protection regulations as well as prevent one of the leading causes of data breaches: inadvertent errors by well-meaning employees. Such software can also spot attempted data exfiltration, which can be a sign of malicious insiders or a network that's been penetrated by hackers (see: Ransomware + Exfiltration + Leaks = Data Breach).

Monitoring tools can also help investigate employees who behave badly. "Employee monitoring software that would potentially scan for keywords in correspondence may, where used appropriately, be a powerful tool for employers to ensure that misconduct is identified promptly, even when employees are working remotely," attorneys Nicola Jones, Boris Dzida and Stephanie Chiu of London-based Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer LLP write in a blog post.

While some organizations have a choice about whether to use various types of monitoring software, particular sectors may be required to do so. "Indeed, in the financial services sector, an employer may have a regulatory duty to monitor employee communications," the Freshfields attorneys say.

Work-From-Home Rules

Organizations that previously declined to use such software may be reconsidering, as working from home continues to be the new norm in many industries, and ensuring that employees comply with corporate policies may be more difficult to enforce.

"Employers may also be concerned that remote working will allow inappropriate behavior to go unseen and unchecked," the Freshfields attorneys say.

Already, legal experts warn, organizations should have begun reviewing all existing policies and procedures in light of so many employees now being forced to work from home.

"Ensure that policies, protocols and procedures governing remote-working arrangements, use and monitoring of company resources and devices, BYOD, business continuity and disaster recovery, and incident management and response - including the collection and subsequent processing of personal data in those contexts - are reviewed, updated and effectively communicated to staff," a team of privacy attorneys at Hogan Lovells write in in a post-COVID-19 cybersecurity and privacy guide.

In addition, for any organization that monitors or tracks employees, "such measures will result in employers collecting and processing additional personal data of employees," they note, which may require the data to be handled in certain ways, per local regulations.

What's Legal?

When it comes to workplace monitoring, what's legal? As with so many questions that touch on employees' rights, including privacy, the answer depends in large part on the geographic location in which an employee is based.

In the U.S., for example, legal experts say protections for individuals are scant.

"U.S. law generally allows monitoring of employees provided they have no reasonable expectation of privacy," according to a legal analysis published by Morrison & Foerster. "Generally, this applies if companies have given employees clear notice that they will monitor public areas and technology resources."

The privacy picture looks different in Europe. Under the EU's General Data Protection Regulation, "there is this balance always between privacy and security and making sure that we put in place measures that are proportionate," Jonathan Armstrong, a partner at London-based law firm Cordery, said at Information Security Media Group's virtual Cybersecurity Summit EMEA on July 1.

Organizations must document these measures in a data impact assessment, as well as spell them out in clear policies for employees. "If I'm going to monitor your access to your work network, I have to tell you that; I have to be open with you, and that's one of the core, fundamental principles of GDPR," Armstrong says.

Covert Surveillance in Europe

In the EU, "generally, it is against the law to collect someone’s data or monitor them without them knowing - this is called covert surveillance," according to the Irish government's Citizens Information Board.

"You should only be monitored covertly if you or your workplace are relevant to a criminal investigation," it says, adding that first, there must be a written policy drawn up governing how and why the investigation will be conducted - and must also say that the goal of the investigation is ultimately to work with police and prosecutors - and specifying how gathered information will be stored and protected. "Covert surveillance must be focused and can only last for a short amount of time. If no evidence is found within a reasonable amount of time, the employer should stop the covert surveillance."

Some EU countries are even more strict. "In Germany and other countries with strong works council rights, the implementation of such software will require consultation with, or even the consent of, works councils," the Freshfield attorneys say.

Subject Access Requests Under GDPR

Under GDPR, employees also have a right to make a subject access request to their employer, to receive copies of all records containing the individual's personal information. But many types of software, including Office 365, have built-in monitoring functionality and analytics tools that organizations might not know exists.

"The difficulty with that is if you haven't been transparent and you then get a subject access request - which are all the more prevalent under GDPR - or you get an employee complaining because they've been furloughed or because they've been selected for downsizing, then litigation will result, particularly if those individuals haven't been told clearly that their time is being monitored, and especially if those people have a valid reason," Cordery's Armstrong says. "If they are home-schooling, if they are a single mum, all of these factors will play into a litigation nightmare for organizations, when they haven't gone through the proper steps."

What's Proportional?

The flip side of employee monitoring is that organizations do not need to respond to every perceived problem immediately, especially as employees have been adjusting to working from home.

"Just to give you one example, I know of a CISO who detected a lot of access on an individual's own device, when he got a company-issued device," Armstrong says. "So they say to him [the employee]: 'What's up, is your device broken?'"

The employee's response, he says: "No, my device is quicker than our one at home and my wife's got a really demanding job, so she's got the company-issued device."

In the early days of COVID-19 lockdowns, many organizations chose a path of great leniency, especially as workers were struggling to juggle working from home, childcare, home-schooling and more, he says. "But I think that give and take has to be reduced eventually, particularly because ... gangs are looking out for devices that haven't hit the network, so haven't been patched for three months. … We know that they're looking for vulnerabilities in home Wi-Fi connections. So every organization has to review their risks against that new risk matrix."