Identity & Access Management , Security Operations

Cybercriminal Service 'EvilProxy' Seeks to Hijack Accounts

EvilProxy Bypasses MFA by Capturing Session Cookies

One of the biggest challenges for cybercriminals is how to defeat multifactor authentication. New research has uncovered a criminal service called "EvilProxy" that steals session cookies to bypass MFA and compromise accounts.

See Also: How-to Guide: Strong Security Risk Posture Requires an Identity-first Approach

EvilProxy appeared in early May and has been used in attacks "against multiple employees from Fortune 500 companies," says Gene Yoo, CEO of Resecurity, a Los Angeles-based security consultancy. EvilProxy undermines MFA, which is considered the gold standard for protecting accounts from takeover, he says.

EvilProxy uses a technique called session hijacking that has been employed before by nation-states and cyberespionage groups. The attack involves stealing a session cookie. A session cookie is a bit of information stored by the web browser that lets a particular service know someone is authenticated.

With a session cookie in hand, an attacker can access a service as the victim would without that victim's credentials or an MFA token.

The group has wrapped its cookie interception functionality into an easy-to-use phishing kit that it sells on a subscription basis. It will appeal to larger numbers of cybercriminals, Yoo says.

EvilProxy is already being successfully used against users of services including Apple, Microsoft and GitHub. It can also be configured to target other services, including Google, Apple's iCloud, Dropbox, LinkedIn, Yandex, Facebook, Twitter, Yahoo and WordPress. It's also capable of targeting users of services that are players in the software supply chain, including GitHub, the Python Package Index, RubyGems and NPM, a JavaScript package manager.

That kind of targeting suggests it could be aimed at helping cybercriminals seeking to tamper with or install backdoors in software packages.

"These tactics allow cybercriminals to capitalize on the end users' insecurity who assume they're downloading software packages from secure resources and don't expect it to be compromised," according to a blog post from Resecurity.

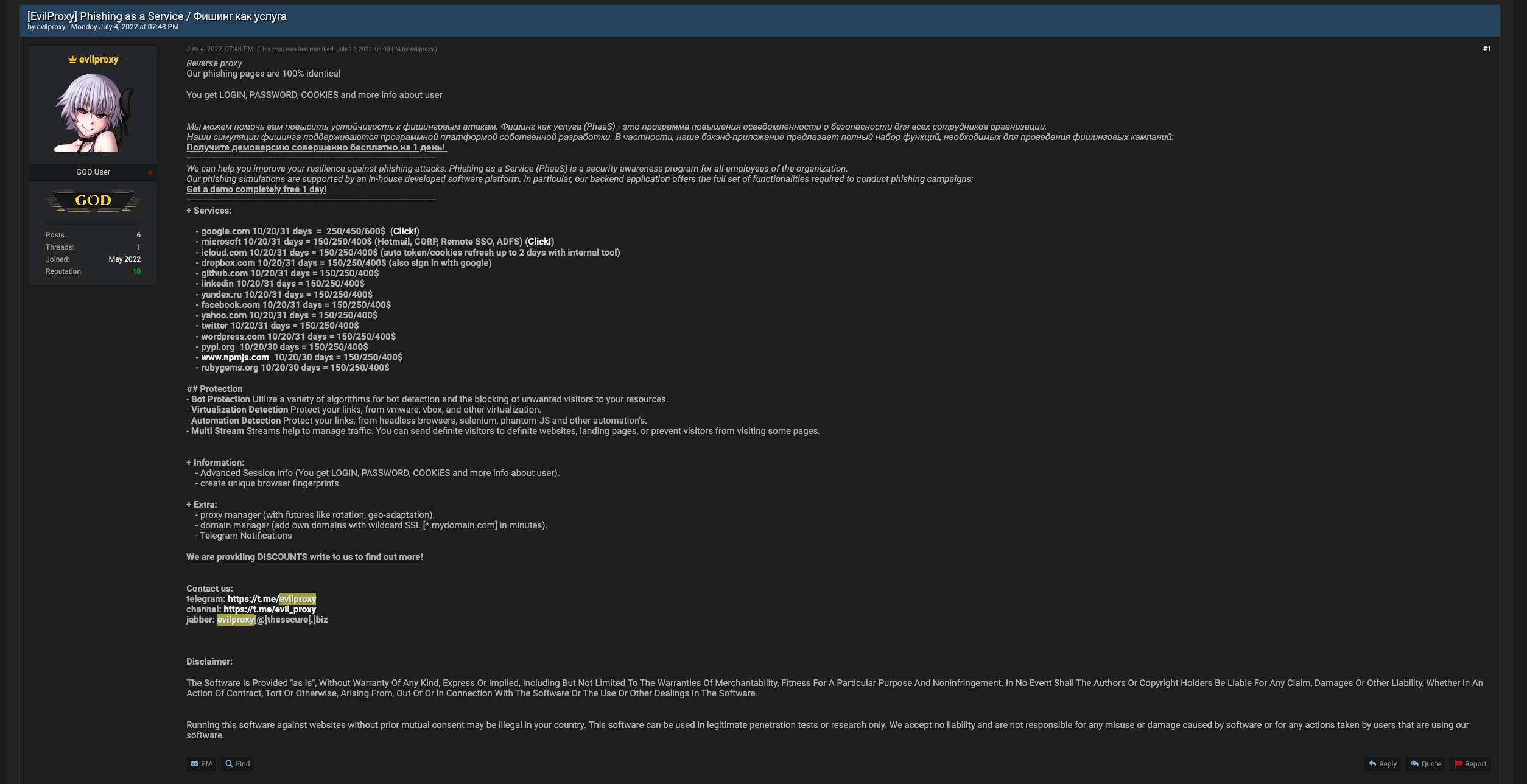

EvilProxy is being advertised on popular crime forums including Breached, XSS and Exploit, Resecurity says. The advertisement somewhat humorously tries to sell EvilProxy as a security awareness tool.

"We can help you improve your resilience against phishing attacks," the advertisement says. "Phishing as a Service (PhaaS) is a security awareness program for all employees of the organization."

Reverse Proxy

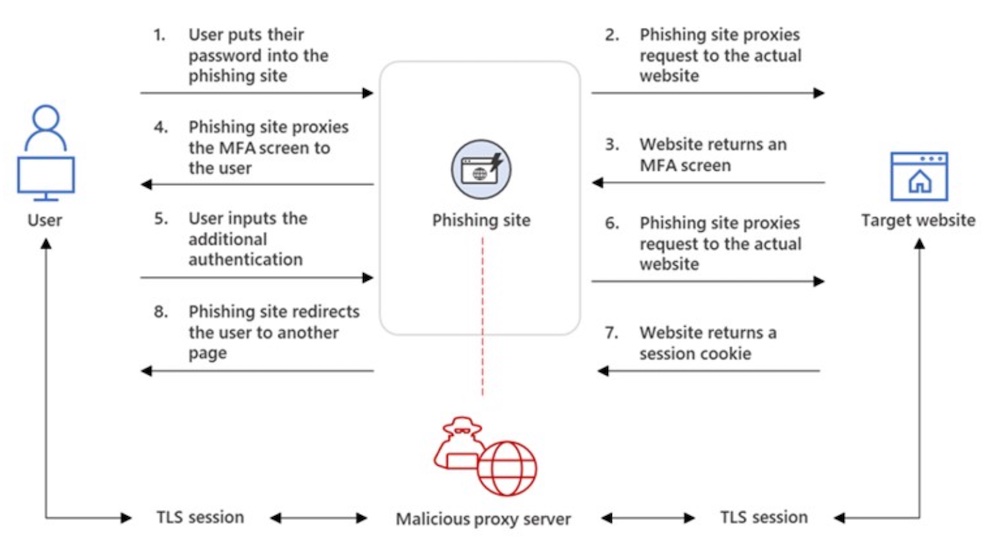

A key part of EvilProxy is its use of a reverse proxy. A reverse proxy is a server that sits in between a phishing site and the real service and can intercept data sent by the real service.

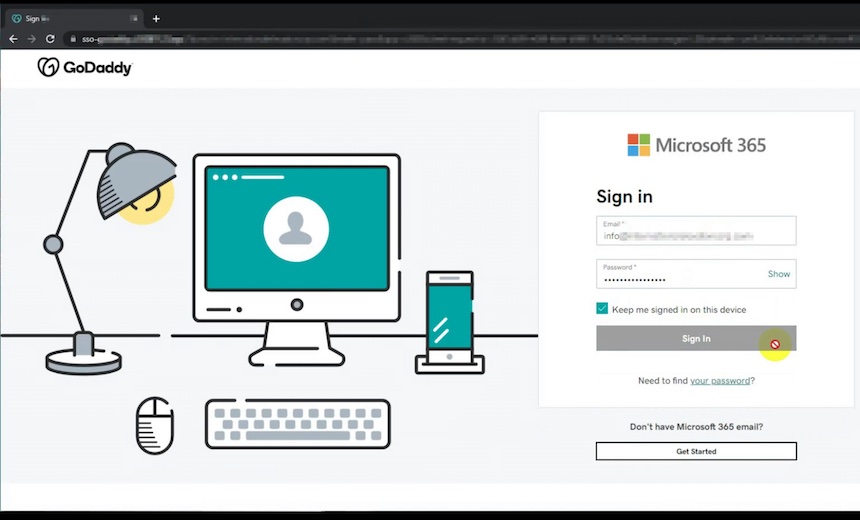

In practice, an attack starts with a phishing link sent to a victim. If the user clicks on the phishing link, the user sees the exact login page as expected.

When a victim logs in, the login credentials and MFA code are passed to the real service. The service then returns a session cookie, which is then captured by the reverse proxy. The attack is also sometimes referred to as adversary-in-the-middle.

"It uses a reverse proxy to fetch all the legitimate content, which the user expects, including the login page, and it sniffs their traffic as it passes through a proxy," Yoo says. "This way they can harvest the actual valid session cookies and bypass the need to authenticate with usernames, passwords or MFA tokens."

Session cookies can be set to expire, but that expiration date is usually past the life of a one-time passcode. Session cookies can be invalidated, however, if someone logs out or by a service provider. But while it's valid, it's a powerful way to continue to access someone's account.

Last month, Okta warned of an uptick in malware that performed session hijacking and allowed attackers to bypass MFA. It also warned of what Resecurity has observed: using social engineering to direct victims to malicious sites configured as reverse proxies.

"These attacks can be effective against user accounts protected only by factors that rely on codes sent via SMS, email or authenticator apps," Okta wrote in a blog post.

Okta says one way to thwart this style of attack is to require a security or hardware key, which ties a physical object to the authentication process that an attacker won't have. Another option is to use a specification such as WebAuthn, which uses public key cryptography combined with secure modules on devices to perform strong authentication without a password.

Brett Winterford, Okta's regional chief security officer for APJ, says some of the features in EvilProxy are available in other open-source phishing kits. But he says that the hosting of adversary-in-the-middle infrastructure "as a service" lowers the entry bar for attackers.

"This is yet more evidence that security teams need to push for stronger authenticators," Winterford says.

Subscription Service

EvilProxy is sold on a per-day basis. For example, an attacker can choose to target Microsoft's login interfaces for 20 days.

EvilProxy generates the phishing URL links, and the attacker is responsible for sending those links out to victims. EvilProxy provides a portal where its customers can monitor campaigns, traffic flow and the data that's collected, according to Resecurity's blog post.

EvilProxy seems to be gaining customers.

"We see an extremely broad clientele," Yoo says. "Cybercriminals, initial access brokers as well as folks with interests close to nation-states because of targets whom they attack."

EvilProxy may be difficult to shut down. Yoo says its operators have deployed the reverse proxies and the phishing sites using the hidden services feature of the Tor anonymity system.

"They're constantly changing the surface of infrastructures - the domains and the hosts used for front end," he says.

EvilProxy comes as cybercriminals are having astounding success routing around two-factor codes and breaking into corporate networks. The security company Group-IB chronicled a recent large phishing attack that it dubbed "Oktapus."

The phishing scheme involved sending SMS messages with links designed to elicit login credentials for organizations that use Okta's identity and access management services (see: Okta Customer Data Exposed via Phishing Attack on Twilio).