Breach Notification , Cyberwarfare / Nation-State Attacks , Email Security & Protection

How Did the Exchange Server Exploit Leak?

Microsoft Investigating; Devcore Pen Testers Say They're in the Clear

It has been an open question as to how a half-dozen hacking groups began exploiting Exchange servers in an automated fashion in the days leading up to Microsoft's patches. But there are strong signs that exploit code leaked, and the question now is: Who leaked it?

See Also: The Cybersecurity Swiss Army Knife for Info Guardians: ISO/IEC 27001

A Taiwanese computer security researcher indicated on Friday that exploit code he developed and privately shared with Microsoft in early January ended up in hostile hands.

The exploit was used to attack tens of thousands of Exchange email servers before Microsoft deployed software patches on March 2. Microsoft is now investigating whether one of its partners is at fault.

Knowing who leaked the exploit information is important because it may provide insight into how a little-known vulnerability was suddenly spun into mass, indiscriminate attacks against Exchange servers in late February. Two weeks on, Microsoft says ransomware is now moving in (see: DearCry Ransomware Targets Unpatched Exchange Servers).

The researcher who developed the exploit code - Cheng-da Tsai, who is known by the handle Orange Tsai - works for the Taipei-based security consultancy Devcore. Microsoft credited Tsai and Devcore with finding two of the four vulnerabilities it patched for Exchange server on March 2.

Tsai tweeted on Friday that attack code analyzed by Palo Alto Network's Unit 42 threat intelligence team was substantially similar to the code that he developed and sent to Microsoft on Jan. 5. He writes that he hardcoded his nickname, which is "orange," as the password for the webshell.

The exploit in later Feb looks like the same, the exploited path is similar (/ecp/<single char>.js) and the webshell password is "orange" (I hardcoded in the exploit...) https://t.co/r4AhKFZjPH

— Orange Tsai (@orange_8361) March 12, 2021

Devcore, however, says it's confident that it did not leak the exploit. Contacted on Saturday, Devcore CEO Allen Own declined to comment but referred to a previously issued statement that an investigation turned up nothing suspicious. Now, attention has turned to Microsoft.

Microsoft: We Didn't Leak, But …

Microsoft says it has found no indications that it leaked the data. But the company is investigating whether one of its partners did. The development was reported on Friday by The Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg.

“We are looking at what might have caused the spike of malicious activity and have not yet drawn any conclusions," the company says in a statement.

Microsoft provides information on exploits and attacks ahead of time to a group of vetted partners that are part of the Microsoft Active Protections Program, or MAPP.

The idea is that giving advance information allows those companies to fine-tune the defenses in their own products ahead of a patch release. The Wall Street Journal reports that Microsoft shared data on the Exchange flaws with MAPP partners on Feb. 23.

A fierce flurry of worldwide attacks ensued. Between Feb. 26 and March 3, 68,000 distinct IPs were compromised, according to The Shadowserver Foundation, a nonprofit organization that investigates malicious activity across the internet. Security experts have warned that no vulnerable Exchange server was likely to have been left untouched in the days before and following the patch release.

“The MAPP program is used successfully ahead of every Update Tuesday cycle," Microsoft says. "If it turns out that a MAPP partner was the source of a leak, they would face consequences for breaking the terms of participation in the program.”

Ten of the 82 MAPP partners are based in China. Microsoft attributed the initial attacks to Hafnium, a group it says is state-sponsored and is based in China. The security firm ESET says now at least 10 APT groups have been exploiting the flaw.

One China-based MAPP partner is Sangfor International, which is one of the largest business-to-business cybersecurity companies in the country. Jason Yuan, Sangfor's vice president of product and marketing, says the company is 100 percent confident it did not leak the data.

Yuan says any source code shared with and received from partners such as Microsoft is regulated by strict access control policies. Just this year, researchers with the company's Sangfor Lights Lab have been credited by Microsoft with reporting 20 vulnerabilities.

"Only a very small handful of individuals within Sangfor have access, and every member of that team is aware of and honor the NDA we have in place," Yuan says. "Source code is only accessible within the company systems and networks, and all access is audited."

A U.S.-based spokesman for Baidu said the company had no comment. Efforts to reach the other eight companies based in China, which include giants such as Alibaba and Tencent, have so far been unsuccessful.

Microsoft has given a MAPP partner the boot before. In May 2012, Microsoft cut off Hangzhou DPtech Technologies Co. Ltd., a company based in China, for leaking data related to CVE-2012-0002.

Luigi Auriemma, the security researcher who found CVE-2012-0002, tells me he was surprised to find that proof-of-concept code that turned up on Chinese forums was the same as what he had developed. Auriemma says there's always the possibility of malicious actors or sloppy handling when sensitive data is sent to third parties.

"Microsoft knows it," says Auriemma, who is CEO of the Revuln conference series and an independent security researcher with Aluigi. "The attackers know it too."

Leak Source May Remain Unknown

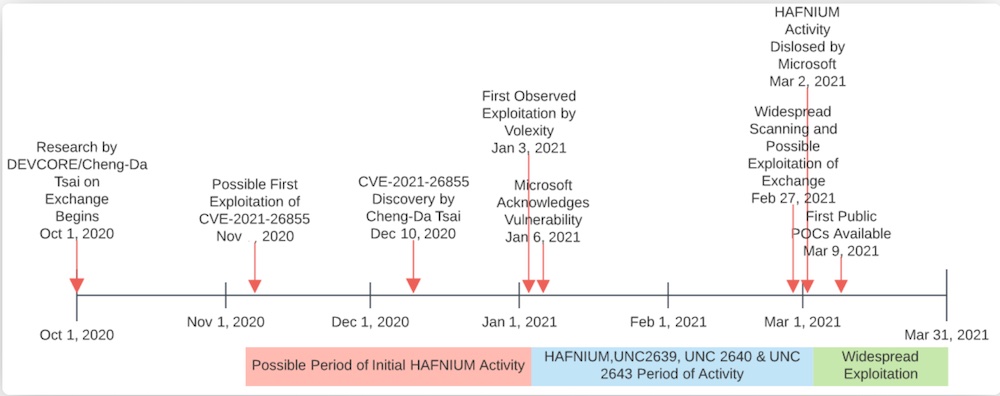

Tsai and Devcore had been looking closely for bugs in Exchange server since October, according to a timeline Devcore published on a website it set up for the flaws, which it groups under the name "ProxyLogon."

The timeline says the first bug, CVE-2021-26855, was discovered on Dec. 10, and the second one, CVE-2021-27065, was discovered on Dec. 30. A day later, Devcore successfully chained the two together for a remote code execution attack.

Tsai and Devcore reported the vulnerabilities to Microsoft on Jan. 5 through its Microsoft Security Response Center portal.

But attacks using CVE-2021-26855 were seen even before then. The security company Volexity says it saw the first attacks on Jan. 3. That's two days before Microsoft received the information from Devcore, making it impossible that either it or a MAPP partner could have leaked it.

Other data suggests that an Exchange attack using CVE-2021-26855 may have occurred as early as November 2020, according to a blog post by Joe Slowik, senior security researcher with DomainTools.

If Devcore indeed was not compromised, the findings from Volexity and DomainTools suggest that perhaps someone else had already found the bug and was using it in a low-key way.

There's a chance we'll never know who leaked it. Although Microsoft's MAPP partners in China are likely in an investigative spotlight, the information could have leaked through a MAPP partner that doesn’t know it has been compromised by attackers.

It's an unsatisfactory prospect that this mystery may not be solved. But it may direct questions back to Microsoft as to whether the MAPP is still worth it. After the 2012 incident, Microsoft defended the benefits of MAPP but acknowledged its risks.

Maarten Van Horenbeeck, who was then a Microsoft senior program manager and is now CISO of Zendesk, wrote a sound justification for MAPP and how it helped participants develop better defenses. But "we recognize that there is the potential for vulnerability information to be misused," he wrote.

As sleepless incident responders around the world continue their work to secure systems, that justification may no longer hold.