Fraud Management & Cybercrime , Next-Generation Technologies & Secure Development , Ransomware

BadRabbit Attack Appeared To Be Months In Planning

Ukraine-Focused Strains of Ransomware Continue to Increase Like Rabbits

Repeat question from this year's NotPetya outbreak: Who's gunning for Ukraine and how many organizations in other countries will be caught in the crossfire?

See Also: Cybersecurity Checklist: 57 Tips to Proactively Prepare

On Tuesday, numerous organizations reported outages that appeared to trace to BadRabbit infections, including the Kiev metro system and Odessa airport in Ukraine, as well as multiple Russian media organizations, including Interfax. Organizations from Bulgaria to Germany to Japan have reportedly also been affected (see BadRabbit Ransomware Strikes Eastern Europe).

"Because BadRabbit is self-propagating and can spread across corporate networks, organizations should remain particularly vigilant," security firm Symantec says in a blog post.

But security experts say the BadRabbit ransomware outbreak appears to have hit Ukraine hardest. Ukraine's Computer Emergency Response Team, CERT-UA, reported that there was a "massive distribution" of BadRabbit in the country.

Security experts say that the simultaneous nature of so many infections in that country suggest that this was a targeted attack and that systems may have been infected well in advance of the outbreak.

It's unclear how many countries may have been affected. Britain's National Cyber Security Center, which includes the country's computer emergency response team, says in a statement that it's tracking the outbreak. "The NCSC has not received any reports that the U.K. has been affected by this latest malware attack," it says. "We are monitoring the situation and working with our partners to better understand the threat." Likewise, US-CERT says that it "has received multiple reports of ransomware infections, known as BadRabbit, in many countries around the world," but has not yet commented on any potential U.S. impact.

Blocking BadRabbit

Numerous anti-virus vendors say their software will block BadRabbit. In addition, Windows administrators can effect a "kill switch" by adjusting the file "C:windowsinfpub.dat" to be read-only, which will prevent the malware from encrypting any files. Mike Iacovacci, a security researcher at Cybereason, has published detailed instructions.

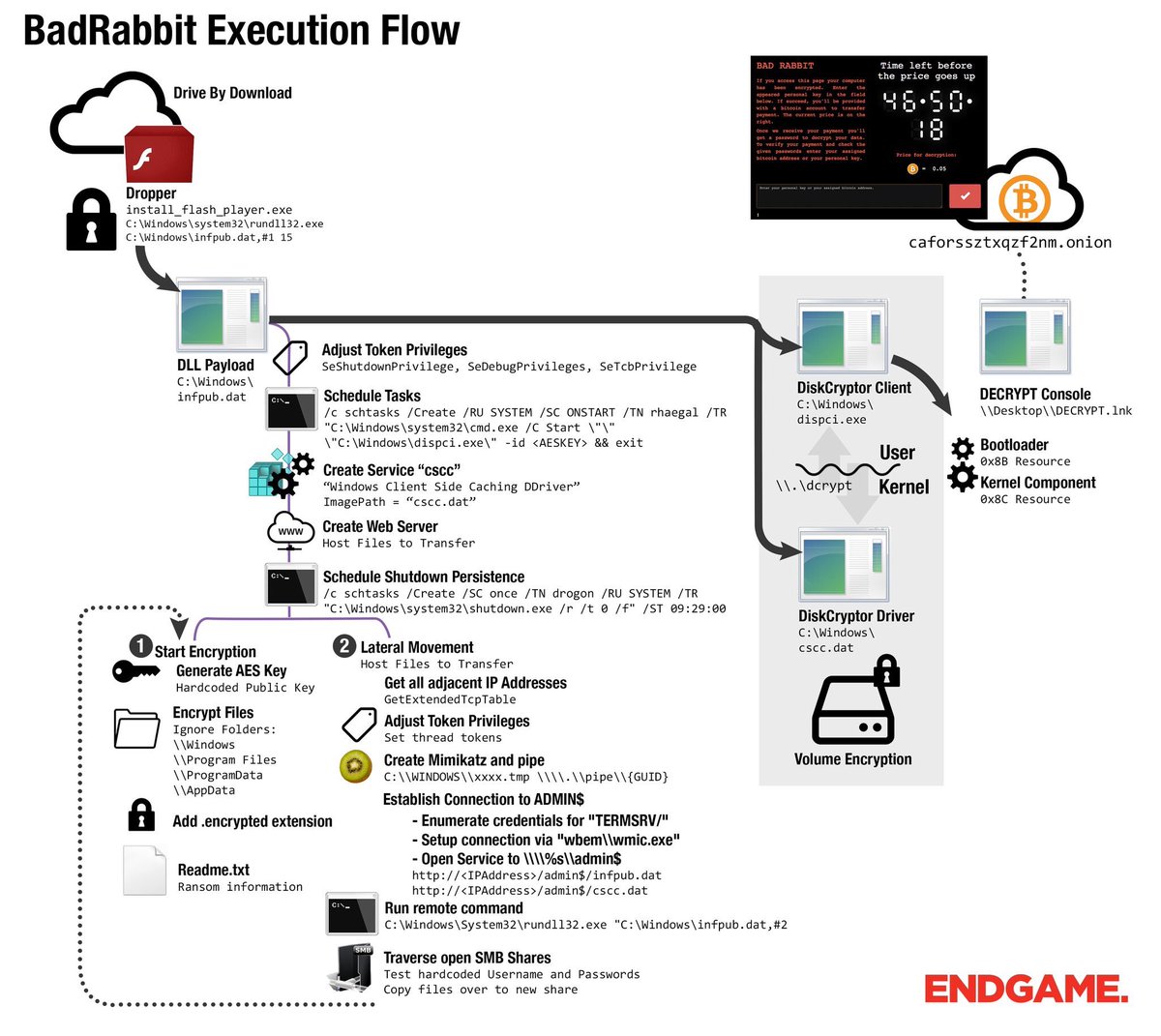

But the BadRabbit outbreak does not appear to have caused damage on the order of this year's WannaCry or NotPetya attacks. "While NotPetya contained a wiper component, BadRabbit interestingly includes the capability of a wiper, but I haven't seen any evidence of its use," Amanda Rousseau, a self-described malware research unicorn at cyber operations platform vendor Endgame, says in a blog post.

Another saving grace for many organizations appears to be that BadRabbit only works if it can trick users. "While WannaCry and NotPetya compromised through more passive victim behavior, BadRabbit requires the victim to actively execute the malicious file," Rousseau says. "This may be why BadRabbit is - at least initially - seemingly more contained than WannaCry or NotPetya."

Strong Ties to NotPetya

Researchers from security firms Carbon Black, ESET and Malwarebytes, among others, say BadRabbit appears to be a variant of NotPetya. Slovakia-based security firm ESET, for example, refers to BadRabbit as Diskcoder.D, and says it's a direct update of Diskcoder.C, aka NotPetya.

"Diskcoder.D has the ability to spread via SMB," ESET says, referring to the server message block protocol built into Windows. But it says an Equation Group exploit for SMBv1 known as EternalBlue is not included. "As opposed to some public claims, it does not use the EternalBlue vulnerability like the Diskcoder.C (Not-Petya) outbreak."

But Cisco's Talos security group says it has found an Equation Group exploit in BadRabbit called EternalRomance, which is another SMBv1 exploit. NotPetya, aka Nyetya, also included an exploit for EternalRomance, although Talos says that the NotPetya and BadRabbit implementations differ.

It's not clear if BadRabbit was built by code-stealing copycats. But many researchers strongly suspect that based on the code and malicious infrastructure, the same group that spawned NotPetya unleashed BadRabbit.

Incident response expert Matt Suiche, managing director of Dubai-based Comae Technologies, says whoever launched BadRabbit appeared to possess the original source code for NotPetya. "Many parts have been improved, deleted and rewritten," he says via Twitter.

BadRabbit is not only similar to NotPetya, it *is* NotPetya recompiled and including bugfixes. See below the lateral movement routine. pic.twitter.com/Pdq6P0TwD7

— Matthieu Suiche (@msuiche) October 26, 2017

BadRabbit marks the fifth Ukraine-focused ransomware outbreak to be seen so far this year. The other ransomware campaigns have involved malware called XData, which looked like AES-NI; PSCrypt, based on Globe Imposter Ransomware; NotPetya, based on Petya; as well as a WannaCry lookalike.

Unlike earlier strains, BadRabbit includes some unique quirks, including peppered references to Game of Thrones, researchers at Moscow-based security firm Kaspersky Lab say. The list of passwords the malware tries to use when spreading includes "love," "secret," "sex" and "god," which as pop culture spotters at the Guardian have noted were the "four most common passwords" named in the 1995 movie "Hackers."

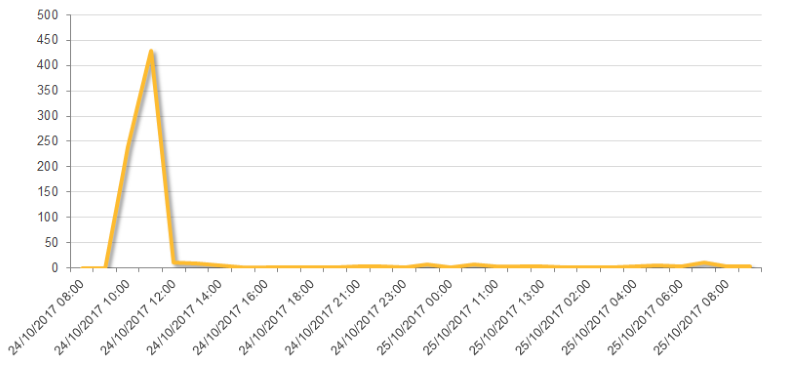

ESET says that Ukraine appears to have been hardest hit by the outbreak, even though the greatest number of infected endpoints were not in that country. Here's where it saw infections hit:

- Russia: 65 percent

- Ukraine: 12.2 percent

- Bulgaria: 10.2 percent

- Turkey: 6.4 percent

- Japan: 3.8 percent

- Other: 2.4 percent

Those statistics are drawn from endpoints and servers that run ESET's software. While other anti-virus vendors have reported similar findings, they say that other countries, including Germany, were also hit by a notable number of infections.

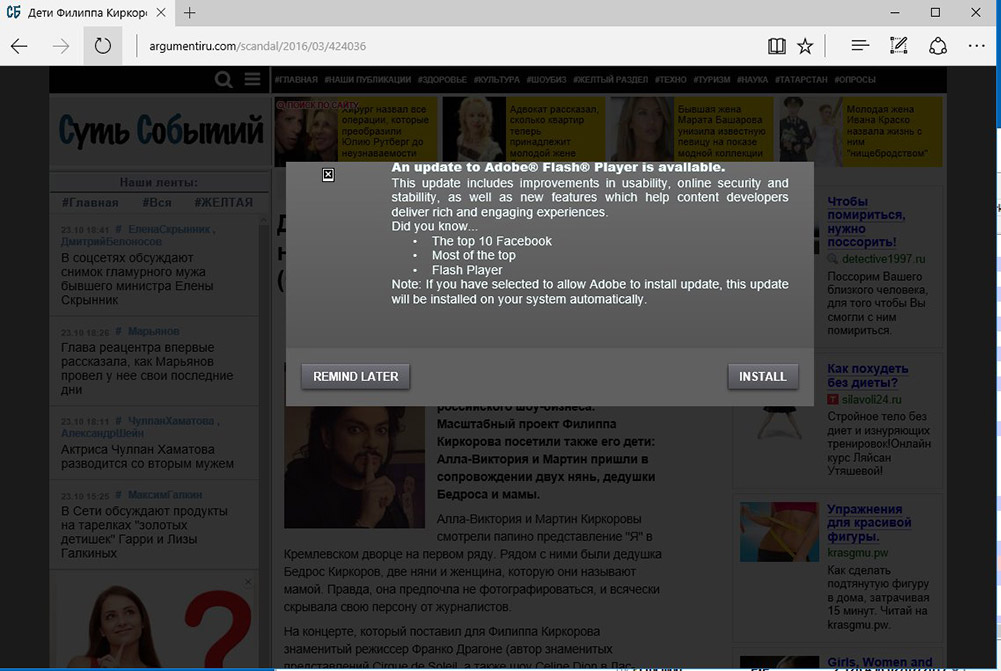

Some security researchers say many of the infections are being spread via drive-by downloads from websites that have been infected by malicious JavaScript in what's known as a watering-hole attack.

"Server-side logic can determine if the visitor is of interest and then add content to the page. In that case, what we have seen is that a popup asking to download an update for Flash Player is shown in the middle of the page," Marc-Etienne M.Léveillé, a security researcher at anti-virus firm ESET, says in a blog post.

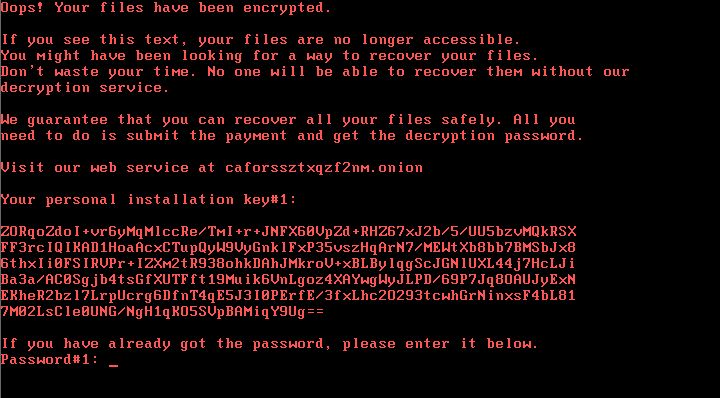

If users click "install," it downloads a malicious "install_flash_player.exe" executable file which serves as a dropper for Diskcoder.D. That ransomware crypto-locks the PC and displays a ransom note directing the victim to an Onion site that demands 0.05 bitcoins - currently worth about $290 - in return for the promise of a decryption key.

Security experts say files crypto-locked by BadRabbit cannot be forcibly decrypted, meaning unprepared victims are stuck having to consider paying the ransom to recover data (see Please Don't Pay Ransoms, FBI Urges).

Two bitcoin addresses that Moscow-based cybersecurity firm Group-IB says attackers are using to receive ransom payments on Wednesday collectively received 0.0027 bitcoins via three transactions. But it's not clear if those might have been ransom payments or intelligence or law enforcement agencies or researchers moving money into the wallets to see where it might go.

Evidence of Extensive Preparation

Costin Raiu, who heads anti-virus vendor Kaspersky Lab's research team, says that hacked sites hosting the watering hole infections have been exploited since at least July.

It appears the attackers behind #Badrabbit have been busy setting up their infection network on hacked sites since at least July 2017. pic.twitter.com/fV5U1FeVtR

— Costin Raiu (@craiu) October 24, 2017

The simultaneous nature of so many of this week's BadRabbit outbreaks, however, could mean they were not infected via watering hole attacks, but rather via direct attacks. "It's interesting to note that all these big companies were all hit at the same time," ESET's Léveillé says. "It is possible that the group already had foot inside their network and launched the watering hole attack at the same time as a decoy. Nothing says they fell for the 'Flash update.'"

Moscow-based cybersecurity firm Group-IB says in a blog post that "the attack at a first glance appears to be financially motivated." In part, that's because attackers have not only demanded ransoms but also taken steps to prevent their attack infrastructure from being disrupted. "For hosting, they used Inferno bullet proof hosting," Group-IB says (see Hacker Havens: The Rise of Bulletproof Hosting Environments).

But attackers may have had multiple motives. Bart Blaze, a threat intelligence researcher at consultancy PwC, says the impetus for BadRabbit may be "as a cover-up or smokescreen, or for both disruption and extortion."

Signs of Long-Running Campaign

Indeed, some of the servers used to inject malware into infected endpoints have been active for more than a year, demonstrating that BadRabbit is "part of a long-running campaign," Yonathan Klijnsma, a threat researcher at security firm RiskIQ, says in a blog post.

Klijnsma also says that any apparent financial impetus behind BadRabbit may be a smokescreen. "The goal of the attack using ExPetya back in June was simple: cause as much disruption in the Ukraine and those associated with Ukraine as possible, which also seems the case in the BadRabbit attack."